The 8th edition of the Zsigmond Vilmos International Film Festival concluded with Mexican short film bagging the top prize

Szeged witnessed a memorable week of film watching with cinema of all shapes and forms handpicked from around the world, screened at the city’s oldest theater, Belvárosi Mozi

Very few film festivals in the world are dedicated to the art of cinematography, making the Zsigmond Vilmos International Film Festival in Szeged a unique standout. In Europe, its only other counterpart is the Camerimage Festival in Poland, which commenced over three decades ago. In comparison, the Zsigmond Vilmos International Film Festival is only eight years old and has managed to carve quite a niche for itself in its short run thus far. The main draw for participants and attendees lies in the name itself – Vilmos Zsigmond, who was born in the city of Szeged in 1930. The renowned cinematographer who won an Oscar for his work in the Steven Spielberg directorial Close Encounters of The Third Kind (1978) was known for his use of natural light and vivid colors, which helped shape the look of Hollywood films in the 70s. His name continues to be a great source of inspiration for cinematographers and filmmakers around the world till the present day, drawing participation from far and wide at this film festival.

The city’s oldest theater, the historic Belvárosi Mozi, played host to this six-day affair (October 7 to 12) that saw a total of 37 films being screened, including the world premiere of Argentinian film Filo Hua Hum, directed by debutant Ernesto Rowe. This theater has a hall dedicated to Vilmos Zsigmond himself, who, until his death, had strong ties to his hometown and was proud that the theater where he saw his first film as a child has a hall bearing his name. The festival opened with a wreath-laying ceremony at his birthplace on Dobó Street, followed by the official opening ceremony at the Zsigmond Vilmos Hall in Belvárosi Mozi. The screenings kicked off with the Hungarian feature Január 2, directed by Zsófia Szilágyi, which traces a day in the life of a woman, Klára, who is getting divorced and moving into a small flat in Budapest from her husband’s home in the suburbs. Through repeated car trips with her friend, wherein they lug an enormous number of bags, the film underscores the stagnation of life despite the constant movements. The locks that open doors to the next chapter in her life are as stuck as the literal rusty locks she tries to open at various points in the film.

The screening was followed by a Q&A with the director and then came more showings of competition films, including MOC/Power, a Hungarian-Slovakian political thriller. The cinematographer of the film, Gergely Pálos, won the prize for the best feature film and the prize from the Association of Hungarian Directors (AHD), which has delegated a jury for the first time in the history of the festival. As compared to last year, this year, the festival saw a large number of Hungarian films screened across categories, such as documentaries, shorts, and feature films – making room for young creative minds to showcase their work on an international platform, especially in the competition segments.

The festival saw participation from around the world, with cinematographers and entries coming in from South Korea, Bhutan, Dublin, Mexico, Argentina, and Costa Rica, to name a few. The international competition section for short films on the third day had some fine entries, such as New Planet (Belgium), which was filmed by Indian cinematographer Anantha Krishnan. It tells the story of an old man who is struggling with grief after the loss of his beloved wife, craving to leave for a ‘new planet’. Tribu from Spain sheds light on the omnipresence of the ‘rape culture’ among young boys and how mindsets are often more powerful than the individual. It went on to win the Best Short Feature Award. The other entries included a short film from China, titled When A Rocket Sits On The Launchpad, that addresses the deep patriarchal forces in China through the journey of an aspiring athlete, while Reminiscence from Lithuania is a psychological drama that plays across two time periods, again addressing the theme of loss. The theme of loss found further expression in more competition shorts, such as Sons of Róisín. Directed by Conor Bradley and filmed by Carlos Moguel, it tells the story of Padraig, who tries to come to terms with the loss of his brother while discovering that his own hearing has deteriorated beyond repair. The ten-minute short brings together an amalgamation of digital and analog footage to integrate certain memory devices with the story to highlight the profound feeling of loss that the protagonist is going through.

This year saw a total of nine feature films, six documentaries, and 22 short films competing for the main prize – the Zsigmond Vilmos Award for Best Cinematography. In the end, it was the Mexican short film Apnea that bagged the prestigious award, with cinematographer José Grimaldo walking away with the highest honor. The strikingly shot film underlines how quickly the lines between love and abuse get blurry in the backdrop of a clandestine relationship between a talented young swimmer, Renata, and her coach, Liliana.

In the documentary category, the jury awarded the prize to Nem Halok Meg (I Won’t Die), which is about the existential journey of a cancer patient, while special mentions were given to The Invisible Frontier (Mexico) and Fairy Garden (Hungary). Later, Gergő Somogyvári, DOP and director of Fairy Garden, also took home the Critics’ Choice Award. Fairy Garden follows the journey of a trans woman for four years as she fights for acceptance and finds her little corner in the world with the help of a compassionate homeless man. Hungarian-Bhutanese documentary Agent of Happiness found a home in the Zsigmond Vilmos Film Festival after a successful run at Sundance. Director-cinematographer duo of Dorottya Zurbó and Arun Bhattarai won the Szeged Award for their film.

For international audiences looking to get a taste of Hungarian cinema, the festival had a fine curation across formats. Aside from a handpicked selection of competition films, under the Hungarian Cinematographers section, films like Árni and Kálmán-nap played to packed audiences. Árni went on to win the Hungarian Cinematographers’ Association (HCA) Award as well as the Vantage Vision Award for the Best Young Cinematographer, which was bagged by Péter Lehr Juhász. Another Hungarian drama, Elfogy a levegő (Without Air), a riveting story about a high school teacher’s fight against archaic mindsets, won the special mention award for Best Feature along with Argentinian film Filo Hua Hum. There was also a 14-member student jury this time, comprising of university and high school students, as well as a Young Critics’ Competition that saw more than 30 entries from around the country.

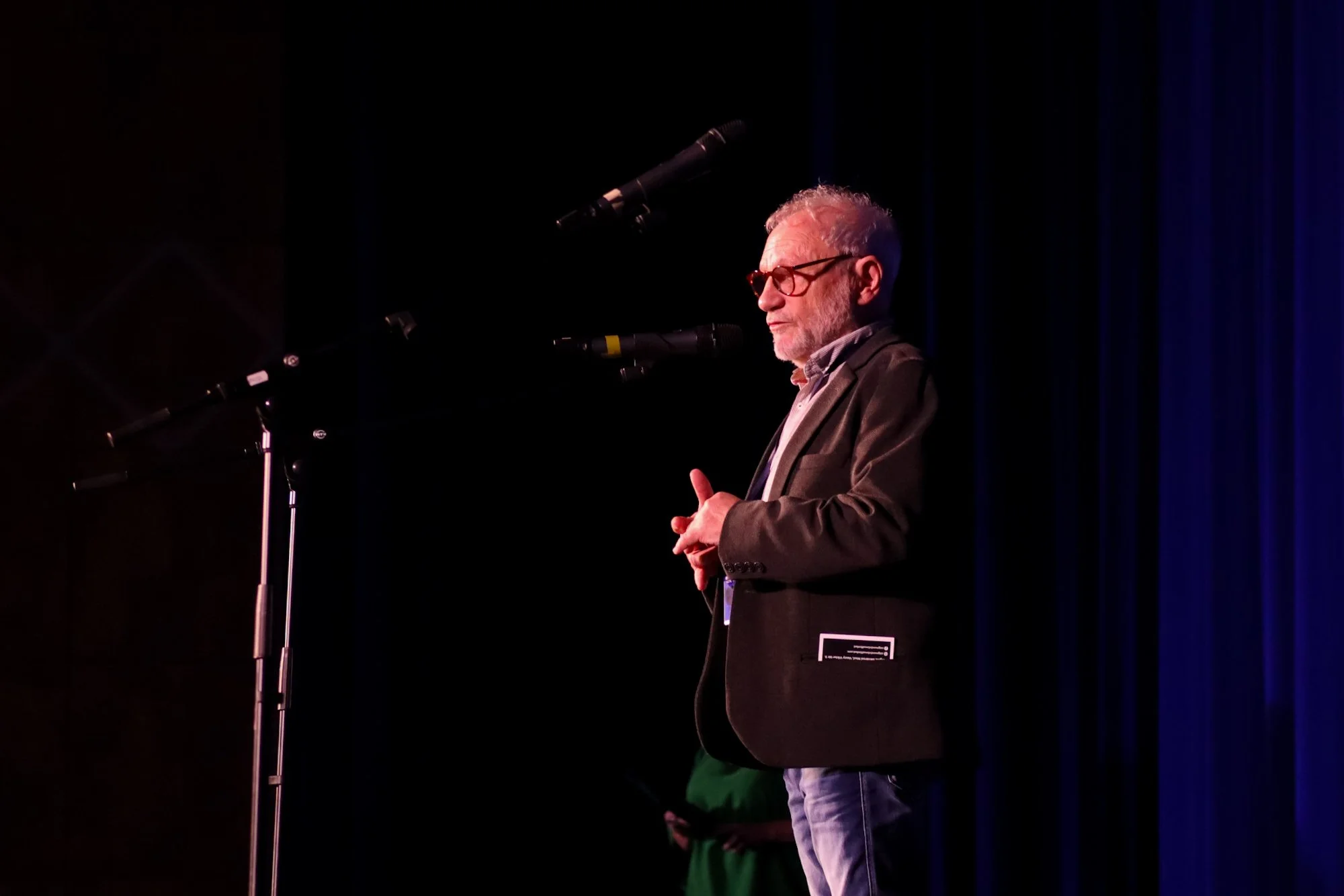

Between screenings, the festival corridors were abuzz with chatter about what’s been watched and what was missed, creatives exchanging notes and anecdotes from their filming experiences between a shot of pálinka or two. The closing day saw a beautiful shadow theater performance to bring the festival to a memorable finish. Speaking of what makes the criteria for selection in this festival, founder and current president of the Hungarian Cinematographers’ Association, Gábor Szabó, said, “This is always difficult as a jury to explain. But good cinematography is not about seeing beautiful images. It’s about how the camera serves the drama of the story, how well the DOP handles the camera, their selection of shots, creation of lighting and atmosphere that make the scenes move. We are not looking for perfection in professional knowledge; many films in the world have that. We are looking for innovative and inventive approaches, wherein the cinematographer does not make it about their individual craft but serves the vision as a whole. And in the end, the film has to be valuable – it needs to carry a message. If the film is strong in itself, the cinematography can enhance it.”

He acknowledges that it is hard to separate the aspect of cinematography from a film in its entirety. “When you watch a film or any kind of complex art form that is made of different pieces if you can tell the pieces apart, then something is wrong with the end product. Even for us, it is hard to separate the DOP’s contribution from the editor, the art director, or the actor. Sometimes you don’t know where an idea comes from – I have also written scenes for films even though I am not a writer. So yes, during the selection process we go through discussions, leading to arguments and disagreements. But that’s the whole process. And outside of the cinematography world, this is hard to explain.”

The team has already begun brainstorming ideas for next year, Szabó adds. “Around the world, the independent film industry is still recovering post-COVID-19. We hope to see more international participation in the coming years. The team is planning to bring in more newer concepts. This year we saw many young filmmakers, especially in Hungary, bringing in some innovative ideas and stories, making films on very low budgets due to lack of state funding. Our aim is to bring in more such films and give these voices a platform.”

Photos: Szilvia Molnar / Szegedify